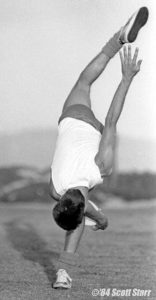

Matt Tips the Disc Under His Leg

Prior to the beginning of the IFA Newsletter in 1968, very little information about the nature of disc play was available to anyone. There is next to nothing about tipping documented before 1968, but no doubt that there were some people doing some tipping somewhere. After all, an integral component of the guts game was tipping and bobbling in an attempt to catch the disc before it hit the ground. After 1968, outside of the guts game, we hear about people tipping, smacking, or slapping the disc up in some manner before making a catch or trick catch.

Alan Blake of the Chicago area Highland Avenue Aces guts team is often mentioned as the earliest of the guys at the IFT to do multiple tips; two, maybe three before sealing the disc. Scott Dickson said that he, Vaughn Frick, and John Sappington were doing some of that kind of tipping as part of their Frisbee play in the early seventies at the University of Michigan; maybe in response to seeing Alan Blake at the IFT, or maybe just as part of their creative way of playing with a Frisbee.

In 1974, some of the very top leaders in Frisbee gathered at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ, for at the first Octad. Berkeley Frisbee Group guys Victor Malafronte and Roger Barrett were in attendance, and so were John Kirkland and Dave Johnson from the Boston area. Jim Palmeri was there from Rochester NY, and of course Gary Seubert, Dan “Stork” Roddick and Bob “Flash” Kingsley, the originators and promoters of the Octad, were there. Another notable Frisbee name in attendance was Jon “JC” Cohn, a Cornell Ultimate star from nearby Maplewood NJ, the birthplace of Ultimate. Rounding out the field was a guy from Philadelphia, a guy from North Carolina, and a whole slew of Frisbee players from the Rutgers Ultimate team, most notably, Irv Kalb. Basically, the forefront of Frisbee play from the entire country was there, and their styles of play accurately represented a good cross section of the state-of-the-art of Frisbee at that point in time. The jamming that these guys were doing in-between the events indicated clearly just what was going down in the various regions of the country. Notably absent from the play was fancy controlled tipping. Despite the fact that the Eastern Trick Catch event to be contested awarded a bonus point for each tip a person completed before doing a trick catch, no one was doing any multiple tipping at all. Occasionally you saw one, maybe two tips at most when the guys were warming up for their Eastern Trick Catch match, but even then, not very often. Because of the strong guts like throws being used as a strategy in the Eastern Trick Catch event, it wasn’t conducive to try for tipping bonus points.

The Eastern Trick Catch (ETC) event had been conceived by Dan Roddick as a way to showcase fancy trick catching skills along with accurate throwing skills. It was the primordial ancestor of the competitive freestyle that subsequently came onto the Frisbee scene. The ETC format consisted of two players standing in twelve-foot diameter circles set 30 yards from each other. Each player in turn would throw the Frisbee to their opponent, such that it would pass through the circle. If the throw was short or outside the 12-foot diameter marking, the thrower would lose a point to his or her opponent. If the throw successfully passed through the circle, the receiver would score one point for a trick catch, and get a bonus point for each time the disc was tipped before making the trick catch. Well, it didn’t take long for the strong accurate throwers like Victor Malafronte, Dave Johnson and John Kirkland to figure out that a blazing hard throw would be difficult to catch, and even more difficult to tip for the bonus points. This strategy went completely against the concept of what Dan Roddick intended for the event, which he duly noticed before that inaugural ETC competition commenced. Guts already existed, and Dan was looking for a kinder-gentler type of game to showcase fancy catching skills, sort of a counterpoint to the guts game. The attempted solution was to lengthen the distance between the circles to 30 yards, figuring that would take the steam out of the fast throws and allow the fancy stuff to commence. It helped somewhat, but it didn’t deter the strategy of throwing hard and fast. The bottom line was that the tipping part of the game was almost nonexistent, and the game failed to be an incentive to learn multiple tipping type moves. So, the fact of the matter was that as of the first weekend of May 1974, controlled consecutive tipping was definitively not part of overall Frisbee play in general. Apparently, no one had seen it being done, and no one was trying to do it. Everyone who knows Victor Malafronte and John Kirkland know that if these two guys had ever seen anything like controlled multiple tipping, they would have immediately sucked it up into their repertoire of Frisbee moves faster than a dry sponge could suck up warm water. If John and Victor weren’t doing a particular Frisbee move, there was a good chance that no one else was doing it either.

At the first American Flying Disc Open event three months later, August, 1974, the same general group of players from the Octad gathered to try to win the brand new car that was being offered as first prize. Other Frisbee notables that hadn’t attended the Octad also showed up. There was a contingent from NYC that included Kerry Kollmar and Mark Dana. From the Chicago area were John Connelly, Tom Cleworth, and Bruce Koger. The University of Michigan guys, Scott Dickson and John Sappington showed up along with some of their Humbly Magnificent Champions of the Universe (aka Humblies) guts team members, including John and Jo Cahow. There were also many new faces to the Frisbee scene; it was Dave Marini’s and Doug Corea’s first Frisbee competition. Kerry Kollmar and Mark Dana sort of set the scene for the incessant jamming that took place all weekend. They induced many of the other players to partake in such jamming. It was a cool scene that included attempts at multiple tipping as a matter of course throughout the play, quite unlike the dearth of tipping at the Octad three months earlier. By the end of the Saturday of that weekend, some of the guys were smitten with trying to outdo each other in seeing how many times they could tip the disc before catching it. Some of the guys were even doing 4 and 5 tips before attempting to catch the disc.

The start of the final round the next day got postponed by heavy rain. Everyone crowded into the St. John Fisher College gymnasium to wait out the rain, and of course jammed to their hearts content. You could barely find a spot in the small gym to throw. John Kirkland introduced an amazing air-bounce throw, which when done well would set the disc to hovering slowly right above the recipient, just begging to be tipped. Virtually everyone was trying their hand at this newfangled throw, and virtually every time one a person received an air-bounce throw, the recipient took advantage of it and tried for a record number of multiple tips. Each new record lasted only minutes as the total number of tips climbed from 5 to 6; then 7, 8, 9 and 10 in short order. The only thing that kept the record from going over ten consecutive tips in a row was that the rain stopped and the disc golfing and DDC commenced. With golf and DDC occupying the players for the rest of the day, no time was left for jamming, and that was the end of the informal tipping contests.

Then two weeks later, at Jim Kenner’s and Ken Westerfield’s Canadian Open Freestyle for Pairs event in Toronto, it became crystal clear that some of the guys had taken multiple tipping to the next level.

In their respective routines, Irv Kalb and Tom Cleworth both showed absolute mastery and control over multiple tipping. They both went from struggling two weeks earlier to get 9 or 10 consecutive tips at the AFDO, to having the number of tips not even being a factor. They could tip the disc until the spin ran out if they wanted to. They limited themselves to maybe 20 or so tips per reception, opting for form and control quality over raw quantity. They both demonstrated that they could pop in an elbow tip or two in the middle of a consecutive string of finger tips. They used their total control to set the disc just in the right position to seal the sequence with a flowing trick catch. It was mind-blowing at the time and a foreshadowing of things to come. Significant to note, that at this time John Kirkland had still had not developed this kind of control in his tipping. But that condition was soon to be rectified, John never settled for second fiddle to anyone for long.

Based on these observations, it seems clear that unlike most facets of disc play, which were often created and developed by two or more people independently of one another and slowly evolved into moves we know of today, the art of multiple controlled tipping had a finite seed of beginning, which can be historically pinpointed. Then with the catalyst of Cleworth and Kalb demonstrating the worth of multiple tipping in a freestyle routine, tipping burst onto the scene in one fell swoop of a revolution, needing no evolutionary process or development for it to catch on. Virtually overnight every Frisbee player who played on a regular basis incorporated tipping into their mode of play. Contrast that with DDC, which started in 1970, but did not get adopted into regular play until 1978. Or disc golf; with the first historically known record of the game being played in was in 1926, but it was not adopted into regular play by the whole Frisbee community until 1974, some 48 years later!

Even tipping’s closest counterpart, the delay, did not catch on immediately. The delay was first publicly demonstrated in August of 1975, (St. John Fisher College again), but did not become widely used until the 1977 competitive freestyle season. Case in point, neither of the number one and two place finishing teams in the 1976 WFC freestyle finals used the delay as part of their routines, they both still used controlled multiple tipping as the connector between moves, a full year after Freddie Haft first displayed the delay move in competition.

Last Article | Next Article coming soon.

Thanks to the Freestyle Players Association (FPA) for sharing this information with FrisbeeGuru.com.

The entire document is stored on FreestyleDisc.org, as is the FPA’s Hall of Fame.

In our recent podcast episode with Joey Hudoklin, he talks about the amazing jam communities in both Washington Square Park and Central Park, New York. We also interviewed Mehrdad Hussanian, who is from Berlin where there is another great jam community. Our jam communities are a big part of what makes Freestyle so great. After work, or the weekend, we know what we’ll be doing…getting together to jam. We push each other to new heights.

In our recent podcast episode with Joey Hudoklin, he talks about the amazing jam communities in both Washington Square Park and Central Park, New York. We also interviewed Mehrdad Hussanian, who is from Berlin where there is another great jam community. Our jam communities are a big part of what makes Freestyle so great. After work, or the weekend, we know what we’ll be doing…getting together to jam. We push each other to new heights.